Impact of Chinese Research “On Par” With U.S.

Research collaborations between China and the U.S. have declined since reaching a peak in 2019.

New data suggests that the United States’ increased focus on research security in recent years may be weakening its competitive advantage over China.

Until around 2018, when the U.S. began increasing its scrutiny of its research partnerships with China and other countries of concern, the U.S. produced far more total research than China. But as of 2024, China produced 878,307 journal articles and reviews in journals compared to 509,485 produced by the U.S, according to a report the Institute for Scientific Information at Clarivate published last week.

In addition to an uptick in volume, the impact of China’s research output has nearly caught up to the U.S.’s—and could even surpass it in the coming years—after years of lagging behind the United States and the world average.

“Competition for the U.S. research system is rising,” Dmytro Filchenko, senior director of research and analytics at ISI and co-author of the report, told Inside Higher Ed. “We can see a shocking trend for China, which for the first time ever is on par with U.S. research.”

The report analyzed academic journal data from 1999 to 2024, including citation impact ratings, total research output and collaborations, for the U.S., China and the European Union, which are the three largest hubs of research activity.

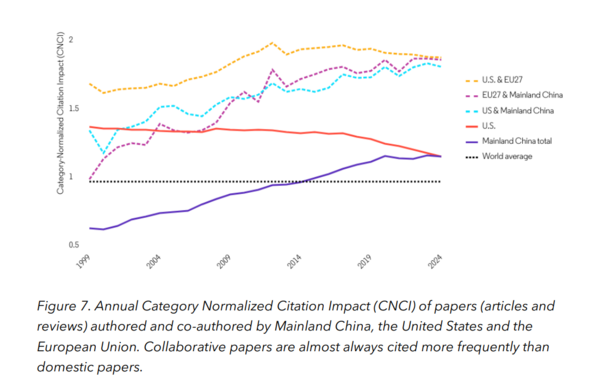

While the data shows that the U.S. remains a global leader in research and development, much of that influence is the result of its international collaborations. Since 1999, papers co-authored by E.U. and U.S. researchers have had the highest Category Normalized Citation Impact (CNCI). Over the past few years, however, the CNCIs for collaborations between E.U. and Chinese researchers and U.S. and Chinese researchers have nearly caught up.

Institute for Scientific Information at Clarivate

“The U.S. research base no longer appears as competitive in global performance as it was in the past. The data show that the U.S. receives a significant academic benefit from collaborative partnerships, which have generated its highest-performing research output,” the report said. “So, if these partnerships decline, then that will be to the further detriment of U.S. research. Mainland China, meanwhile, is continuing to grow its output and to do so to a high academic standard.”

Since the 1940s, U.S. investment in research has made it the global leader in scientific innovation. Beginning in the 1990s, international research collaborations became increasingly common. Up until the 2010s, the top research partner for the U.S. had been the United Kingdom. By the mid-2010s, however, China had taken that spot, and collaborative production peaked in 2019. That year, roughly 30 percent of research papers in tech fields produced by U.S. scholars included Chinese co-authors, a 50 percent increase from the early 2010s.

Although China is still the U.S.’s top research partner, between 2019 and 2023, U.S.-China collaborations decreased by 25 percent before leveling off last year. Meanwhile, China’s collaborations with other major research producers, including the U.K., Australia and Germany, are all on the rise after dipping during the pandemic.

Institute for Scientific Information at Clarivate

Aside from the decline in research partnerships with China, U.S. collaboration with other nations, including Germany, Canada and France, is rebounding to pre-COVID levels. Partnerships with India and Saudi Arabia, although still limited, never dipped during COVID.

Institute for Scientific Information at Clarivate

The report attributes the drop in U.S.-China collaboration to heightened federal scrutiny of U.S. academic and research partnerships with China as part of a broader national security push that started during the first Trump administration, as well as flat research funding in the U.S. compared to China’s record investments in its research enterprise.

“For the U.S., the outcomes of reducing engagement with Mainland China are presumably balanced against security unease,” the report said. “The consequences of more widespread disengagement, particularly with countries/regions that are themselves rising economies and potential research drivers, would be of more general concern.”

According to another recent calculation by an American Association for the Advancement of Science researcher, in 2023 China was already on track to outpace U.S. spending on research and development.

“The United States appears in decline as a research partner: its growth has weakened; its citation impact is falling; it may be losing its dominant lead in global research,” the ISI report said. “Recent policy statements regarding its overseas links point to negative implications for its own research future and for global networks.”

Although the report’s analysis ends in 2024, before President Donald Trump started his second term in January, experts say the second Trump administration’s policy initiatives aren’t likely to help the U.S. reassert its dominance over China. Over the past year, the administration has further restricted international student visas and moved to slash the federal research and development budget.

“This report is one more data [point] that policymakers need to take seriously to understand that America’s scientific leadership wasn’t by accident,” Chris Glass, an education professor at Boston College, said. “If it maintains a passive attraction policy as opposed to an active recruitment policy, it risks surrendering its long-held advantage in science.”