ROI Starts on Day One

Mordecai Brownlee’s body hurts. Last week he trekked three days and 71 miles along Denver’s High Line Canal to raise $90,000 in emergency funds for Community College of Aurora students’ basic needs. “ROI starts with stability,” the president of CCA said this week in Atlanta at Inside Higher Ed’s Student Success US 2025.

Brownlee’s mission shows how far some leaders will go to make sure their students are given every opportunity to succeed. His definition of return on investment was one of many voiced by student success leaders at the event.

Return on investment is often conflated with value. And these days, most Americans don’t believe in the value of a college degree—only 35 percent rated it “very important” in a recent Gallup poll, down from 75 percent who viewed it that way in 2010. Proposed solutions to the value problem often focus on graduates’ earnings. Speaking at Hillsdale College in September, Education Secretary Linda McMahon said degrees must provide a clear return on investment. “College is not a place to ‘find yourself’—but to equip yourself for a concrete vocation,” she said.

Getting a return on their financial investment is critical for students, but what student-focused leaders like Brownlee understand is that students invest more than just money into their education. They see that vibrant campus communities hinge on engaged students who invest time and energy at campus events, volunteering and contributing to student organizations. Time in class means time not earning wages or upholding caring responsibilities—these opportunity costs of attending college are often overlooked.

Many institutions are thinking about evaluating ROI in terms of a sense of belonging, along with traditional interventions like raising money for tuition assistance and scholarships. They recognize that students are betting their futures—and very often those of their families—on their educations. Beyond just putting graduates on a career path, a college degree can lift students out of poverty and help them build generational wealth.

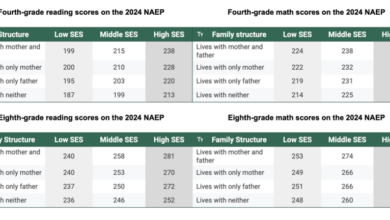

Yet despite efforts such as Miles with Mordecai, higher ed as a whole struggles to deliver on students’ nonmonetary investments. One issue is access. In 2017, research from economists based at Stanford, including Raj Chetty, challenged higher ed’s promise of helping students achieve the American dream. Though many have argued against judging the value of a degree based on income quintiles, the data found that only low- to middle-income students who attended private, highly selective colleges made significant moves up the income ladder and earned more than their parents.

Another indicator that colleges aren’t delivering early returns comes from an Inside Higher Ed student survey from July. It found that 36 percent of students lose trust in higher ed after they enroll, likely reflecting their disappointment with their campus experience. IHE’s main Student Voice survey of more than 5,000 students also found that nearly three-quarters of students rate their sense of social belonging as “average,” “below average” or “poor.” Their sense of belonging in the classroom improves among all students—61 percent rate it average or above. But first-generation students were more likely to rate their sense of academic fit and social belonging as “below average” or “poor” compared to their continuing-generation peers.

More recent studies from Chetty and colleagues point toward a solution: They found that the best way to improve economic opportunity and narrow racial and socioeconomic disparities is to combine financial support with social capital, such as connections to employers or college counselors.

Thinking of ROI as only what students earn several years after investing a relative fortune in obtaining their degree is too narrow. Showing students a return on their investments now—through high-touch support and financial aid—will help them persist, graduate and ultimately achieve the long-term returns everyone seeks. Perhaps it’s time more institutions took that message to heart—even if they don’t need to walk 71 miles to prove it.